Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Architectural Symbolism 101: Geometry

Classical architecture has a rich and intricate symbolic repertoire reaching back to earliest recorded history that today can be compared to ancient Latin: a language once in common currency but today understood only by a few adepts. Well into the 19th century, the educated viewer could read a building as one reads a book, but today the language of classicism is largely mute to us, much of its meaning lost and eroded by time and the relentless evolution of human societies.

The first step in deciphering the meaning of the built world is to understand a structure's geometry—both its two-dimensional plan and in three dimensions. The origins of geometry—literally, "the measure of the earth"—are as obscure as the origins of civilization, and much that was "discovered" by the likes of Pythagoras was actually obtained from the priestly caste of ancient Egypt—their own knowledge so lost in the mists of time that it was attributed to Toth, god of language and knowledge—and was simply openly disseminated by the Greeks for the first time.

Pi, for example, often attributed to Archimedes, is clearly encoded in the measures of the Great Pyramid of Giza (and was also known in ancient China, the Indus Valley and in Sumer). Likewise, the symbolic meaning of geometry and number can be traced through the Greeks and the other ancient civilizations of the Mediterranean basin to Egypt and Sumer, and when we continue farther in time we encounter the evidence of monolithic civilizations destroyed by the last ice age, about which so much has been projected and too little known. The point here is to identify the origin of the symbolic meaning of geometric figures: Egypt, transmitted to us via the Greeks and their neighbors.

We will use a very simple example to illustrate geometry's symbolic power: the Bosquet of the Three Fountains in the gardens of Versailles (depicted in the watercolor reproduced at the top of the post). This elaborate garden-within-a-garden was built in the early 1700s by order of Louis XIV, and tradition holds that the king acted as his own architect and directed the bosquet's design.

The bird's-eye-view watercolor above was commissioned by the Société des Amis de Versailles to aid in fund-raising efforts to rebuild the bosquet. As you can see, the garden is laid out on three levels: each parterre with its central fountain is linked by grass steps, ramps and low cascades to the level below. Like the other baroque bosquets in the park of Versailles designed for Louis XIV, the Three Fountains is rigidly geometric and features elaborate water displays.

Though difficult to see in this small reproduction, the highest, farthest fountain has a circular basin; the middle basin is square and the lowest is octagonal. And here we have the crux of the bosquet's symbolic meaning: the circle (and its three-dimensional counterpart the sphere) represents the arcing vault of the heavens.

The square represents the earth, literally its four "corners," or cardinal directions (as well as the four known continents of the Renaissance age: Europe, Asia, Africa and America).

Finally, the octagon is the symbol of kingship, standing halfway between earth and Heaven, the square and the circle—a perfect geometric form that perfectly incarnates the French conception of the sovereign as the essential mediator standing midway between God and the people.

The traditional method of constructing an octagon begins with a square, upon which one inscribes the arc of a circle. Constructing an octagon also generates an infinitely regressing triangle, further adding to the figure's symbolic power (in fact, Louis XIV became linked to Descartes' idea of a centered infinity—with himself as the central point from which infinity was referenced, of course).

You will also notice that Louis XIV did not place the octagon between the circle and the square, as one would expect, but rather he employed it as the summation of a progression, or an equation: Heaven (circle) and earth (square) give rise to the king (octagon). And here we have a simple but profound insight into the mind of the Sun King: unsurprisingly, he considered himself and his position as the summation of the union of Heaven and earth, rather than as the mediator between them. No one ever said Louis XIV was afflicted by self-doubt.

Finally, what we have here is a perfect symbolic expression of absolutism—no surprise really, as the bosquet was conceived by the man who literally defined the age. France, in the Age of Louis XIV, superceded Italy to claim first place among the powers of Europe in all spheres, including for the first time, culturally. Though it used the art and architecture of Italy as its template, France constructed its cultural hegemony upon the foundations of absolutism, not humanism, and Leonardo's humanist vision of man as the center and measure of all things was replaced by the idea of a single man—a king.

Thursday, July 7, 2011

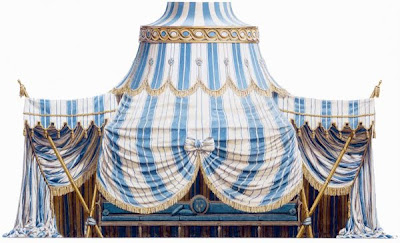

Garden Tents

One of the most evocative symbols of summer is the garden tent, so it's the perfect subject for July's first post.

In the late eighteenth century, Europeans considered tents the most characteristic of Oriental structures and erected them prolifically in their gardens, indiscriminately labeling them as Tartar, Turkish, Siamese or Chinese. There was a kernel of truth in this notion since nomadic tents are indeed the origin of the Chinese pagoda's characteristically concave, upturned roof—though it is highly doubtful that any European gardener of the period knew this.

As picturesque as they were inexpensive, tents became a staple of Anglo-Chinese folly gardens and a number of them, such as the Tartar Tent at the Parc Monceau in Paris (above) were even constructed of permanent materials. Sheathed in trompe l'œil tole-work (painted tin sheet-metal), this tent was actually an open-air alcove and part of a wing added to the main pavilion; dense plantings to either side hid the connecting passageways from view. Built circa 1775, it was also the first of its kind, inspiring similar tole-work tents at the Désert de Retz and at Haga and Drottningholm in Sweden.

The Parc Monceau, the Duc de Chartres' folly garden, which today is a Parisian city park, also featured this extraordinary draped canvas tent (above); nearby was a stand with turbaned lackeys offering camel rides (below).

These engraved scenes of Monceau by Carmontelle, the park's designer, are among our favorites: they carefully record the slightly mad clutter of this Ancien Régime Disneyland and are peopled by elaborately clothed and bewigged visitors, perfectly capturing the atmosphere of slightly absurd refinement that reigned in French folly gardens. Just how self-consciously aburdist or surreal Monceau actually was is in fact quite difficult to judge; consider, for example, that no structure was more characteristic of the countryside of the period than a windmill just like the folly depicted in the lower view—it would be comparable to building a suburban split-level in a landscape garden today.

Ephemeral garden tents became extremely fashionable at Versailles during the reign of Louis XVI, as their ease of construction, inherent theatricality and low cost made them the perfect foil for the numerous, equally extravagant fêtes hosted by Marie-Antoinette at Trianon. Elaborate garden parties, often spanning a week's festivities, were an ancient royal tradition and were first mounted at Versailles by Louis XIV in the late 1600s. In contrast to the baroque pomp of the Sun King, Marie-Antoinette transformed the landscape gardens of Trianon into a rustic, illuminated wonderland for her famed evening garden parties. (Below, the Belvedere during one of these "illuminations.")

Popular rumor was such that after the Parisian mob stormed Versailles in 1789, among the first demands of the deputies of the Third Estate was to examine the Queen’s garden tents, which they believed fashioned of precious fabrics encrusted with gold and silver. The reality, retrieved from the store rooms of the Menus plaisirs, was more worthy of the stage than royalty: painted canvases hung with pasteboard decorations.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)